Annals of Cardiology and Vascular Medicine

HOME /JOURNALS/Annals of Cardiology and Vascular Medicine- Case Report

- |

- Open Access

A novel use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in the management of prosthetic valve thrombosis during pregnancy

- Rizwan Attia;

- Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, 6th Floor East Wing, St Thomas’ Hospital, UK

- Kings College London, London

- Xun Luo;

- Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, 6th Floor East Wing, St Thomas’ Hospital, UK

- Kings College London, London

- Victoria Asfour;

- Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, St Mary’s Hospital, UK

- Vinayak Bapat

- Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, 6th Floor East Wing, St Thomas’ Hospital, UK

- Kings College London, London

| Received | : | Oct 23, 2018 |

| Accepted | : | Nov 12, 2018 |

| Published Online | : | Nov 15, 2018 |

| Journal | : | Annals of Cardiology and Vascular Medicine |

| Publisher | : | MedDocs Publishers LLC |

| Online edition | : | http://meddocsonline.org |

Cite this article: Attia R, Luo X, Asfour V, Bapat V. A novel use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in the management of prosthetic valve thrombosis during pregnancy. Ann Cardiol Vasc Med. 2018; 3: 1011.

Abstract

Switching from Coumadin-based to heparin-based anticoagulant for management of mechanical heart valves during pregnancy carries risks. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO) may play a role in urgent or life-threatening clinical conditions for resuscitation prior to surgery. A 27-year-old 28-weeks gestation primigravida presented with dyspnoea. Past medical history included mechanical mitral valve replacement following infective endocarditis. At the start of pregnancy the patient had switched from warfarin to twice daily enoxaparin. Computer tomographic pulmonary angiogram was normal. Rapid deterioration with respiratory failure and cardiogenic shock ensued. Transoesophageal echocardiogram demonstrated thrombosis of the mechanical prosthesis. Veno-venous ECMO was initiated to improve gas exchange; this was converted to veno-arterial ECMO for circulatory support. Fetal heart sounds were undetectable and diagnosis of stillbirth was made. 5-hours after stabilisation the patient underwent redo mitral surgery. The patient was weaned from ECMO 7-days post-operatively. The patient had medically induced delivery of the fetus. She was subsequently discharged from hospital after a 20-day stay. She remains well at three-year follow-up. Anticoagulation during pregnancy is complex, and prone to complications. Cardiogenic shock and respiratory failure due to prosthetic valve thrombosis can be managed effectively with ECMO, providing a temporising measure to correct the patient’s gas exchange and provide haemodynamic stability before high-risk redo surgery.

Keywords: Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; Pregnancy; Mechanical heart valve; Valve thrombosis

Introduction

Anticoagulation of mechanical heart valves during pregnancy is a complex and contentious issue, maintaining therapeutic range whilst simultaneously avoiding maternal and fetal complications. We present a case of inappropriately managed anticoagulation in the antenatal period resulting in Prosthetic Valve Thrombosis (PVT) with associated respiratory failure and use of ECMO for resuscitation prior to emergency surgery.

Although it is unusual for a woman of childbearing age to require a valve replacement, there will be occasions when this is so. Mechanical prostheses last longer than biological prostheses and are usually favoured in the younger population to minimize need for reoperation but carry risk of thrombosis [1]. Oral anticoagulation with a vitamin K antagonist is mandated [2]. If the woman wishes to start a family or becomes pregnant the medications need to be reviewed [2]. Current methods of anticoagulation carry different risks to both mother and fetus. Warfarin carries risk of teratogenicity. Fetal effects can include frontal bossing, midface hypoplasia, saddle nose, cardiac defects, short stature, blindness and mental retardation. It increases the risk of pre-term labor, pre-partum and post-partum haemorrhage. It is therefore recommended to avoid it in the first trimester and around the time of delivery. Low molecular weight heparin is the favoured agent for anticoagulating pregnant women with prosthetic heart valves but there is limited safety data [3]. Due to suboptimal anticoagulation, difficulties in compliance, and a physiological hypercoagulable state, pregnant patients are often more vulnerable to complications, such as prosthetic valve thrombosis, valvular regurgitation or even systemic emboli [4]. Severe cases of prosthetic valve thrombosis may result in cardiopulmonary failure with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), especially complicated in pregnancy due to different physiology, and the challenge of protecting both mother and fetus. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO) has shown benefit in pregnancy [5].

There have been multiple accounts in the literature describing the role of ECMO in pregnant and postpartum women. During the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, ECMO was utilised for the treatment of severe ARDS refractory to standard treatment, with a 66% survival rate, a figure consistent with multiple studies assessing the effectiveness of ECMO in a mainly nonpregnant population group [5]. Whilst currently underutilised in pregnancy due to concerns about bleeding, ECMO has been observed to show benefit in preventing both maternal and fetal hypoxemia in cases of severe cardiopulmonary failure where more conventional methods of oxygen delivery are insufficient [6].

Case Report

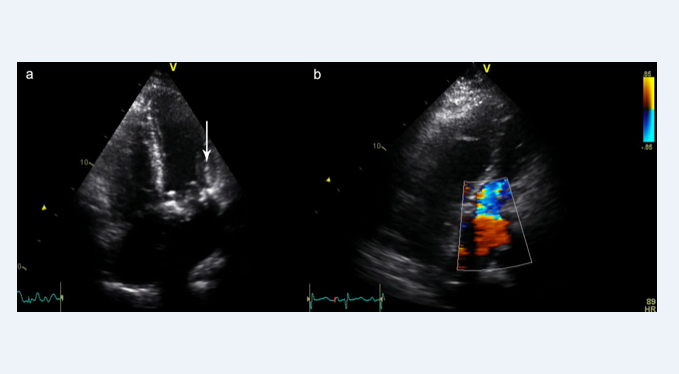

A 27-year-old primigravida (28+2) presented to local emergency department with severe dyspnoea (NYHA IV). Several days prior to admission she had been prescribed antibiotic therapy for suspected community acquired pneumonia. The patient was commenced on intravenous antibiotics for the pneumonia. The working diagnosis was a pulmonary embolism and the patient was scheduled a Computer Tomography Pulmonary Angiogram (CTPA). Ultrasound confirmed live fetus. The patient had previously undergone Mitral Valve Replacement (MVR) with a bileaflet mechanical prosthesis for infective endocarditis 6-years ago, and at the start of pregnancy had substituted warfarin (with a therapeutic target INR 2.5-3.5) for therapeutic dose subcutaneous enoxaparin. A Transthoracic Echocardiogram (TTE) demonstrated no clear abnormalities but the patient developed pulmonary oedema, refractory hypoxemia and raised venous pressures. Diagnosis of cardiogenic shock secondary to Prosthetic Valve Thrombosis (PVT) was suspected. The patient rapidly developed respiratory failure with refractory hypoxemia. It was decided that she would need Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO), requiring a referral to her nearest ECMO centre for additional Intensive Care Unit (ITU) support and assessment for possible caesarean section and delivery of the fetus. She was intubated, placed on Veno-Venous (VV) ECMO using femoral 25Fr multistage Medtronic cannula, 17Fr Medtronic internal jugular cannula and 23Fr Medtronic single stage venous return cannula, using the Maquet CARDIOHELP ECMO system (Getinge Group, USA). She was then transferred to the ECMO centre. Upon transfer repeat scan demonstrated intrauterine fetal death. Transoesophageal echocardiogram (TOE) confirmed a thrombosed mechanical mitral valve (Figure 1).

Due to haemodynamic instability the VV-ECMO was converted to Veno-Arterial (VA) using femoral arterial Medtronic Biomedicus 19Fr cannula to achieve haemodynamic stability. Flows of 3.97Lmin-1 were achieved with rate of 2545rpm, with mixed venous oxygen saturations of over 70%. The patient was on milrinone (0.375-0.5mcg/kg/min) and noradrenaline (0.2- 0.3 mcg/kg/min) and after a period of medical optimisation went for high-risk (logistic EUROSCORE 38.66%) redo mitral valve surgery.

Operation

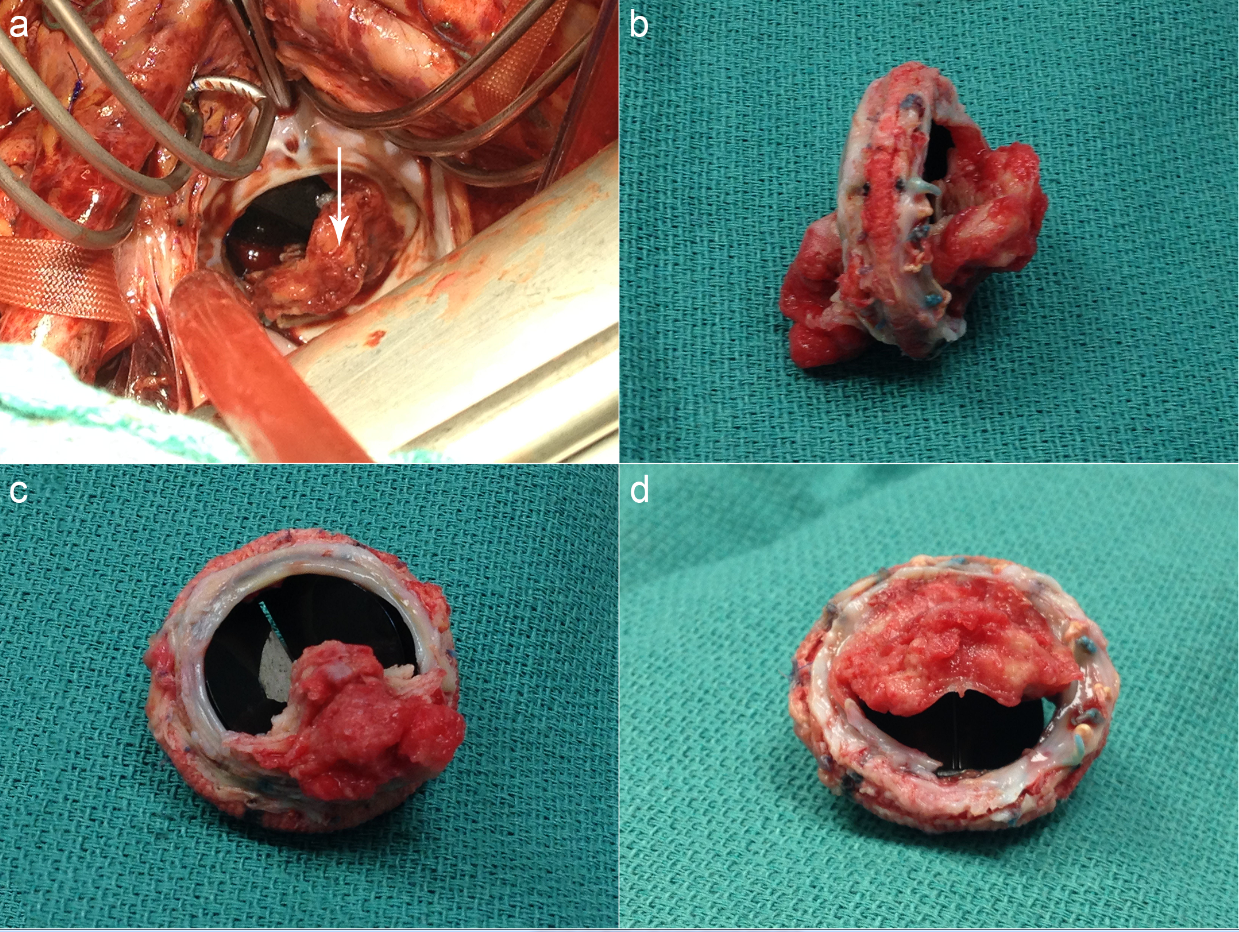

VA-ECMO was via. the right femoral artery and left femoral vein and right jugular venous cannulation. This was used to establish Cardiopulmonary Bypass (CPB), and a redo-sternotomy was performed. After dissecting adhesions to free the aorta and right side of the heart, antegrade cold blood cardioplegia was used to arrest the heart. The left atrium was opened via. paraseptal incision, exposing mitral valve and thrombus (Figure 2).

Figure 2: (a) View into left atrium, with mitral valve thrombus in situ (arrow). (b) Excised mitral valve, thrombus extending entirely through narrow orifice. (c) Excised mitral valve, view from left ventricle. (d) Excised mitral valve, left atrial view.

The valve was completely excised and replaced with a Carpentier-Edwards 27mm Perimount bioprosthesis using interrupted pledgeted 2/0 Ethibond sutures. The operation was uneventful with a cross clamp time of 77 minutes and cardiopulmonary bypass time of 204 minutes. VV-ECMO using Levitronix CentriMag® was restarted at the end of the operation due to an inability to maintain satisfactory saturations with full ventilation. Heparin was hence partially reversed. The patient remained on ITU with inotropic and vasopressor support (Dobutamine (20mcg/ kg/min) and noradrenaline (0.2mcg/kg/min)) for 48-hours. The patient had a loading dose of levosimendan (12micrograms per kg) with a maintenance dose for 24 hours (0.1mcg/kg/min). She was weaned off ECMO after 7-days. During her postoperative ITU stay the patient developed a stenotrophomas pneumonia that was managed with intravenous co-trimoxazole (1.44grams over 24hours) and fluconazole (400mg daily). Delivery of the fetus was medically induced on day-8 and the fetus was successfully delivered vaginally the following day. The patient had an inpatient stay of 20-days post-operatively and was discharged home well.

Discussion

Anticoagulation in pregnant patients with prosthetic heart valves involves striking the right balance between protecting the mother from thrombotic complications, and adverse effects to the fetus, such as embryopathies, bleeding and miscarriage [7].

Current National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines suggest aiming for an International Normalised Ratio (INR) of 2.5-3.5 with oral anticoagulation [9], depending on prosthesis thrombogenicity and associated risk factors. Women who become or are thinking of becoming pregnant are advised to switch to low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) [9], whereas the European Society of Cardiology guidelines suggest both maternal and fetal risks should be weighed up in determining anticoagulant of choice for the 1st trimester, followed by oral anticoagulants in the 2nd and 3rd trimesters [9]. Patients who are switched to LMWH require regular monitoring of anti-Xa levels, aiming to maintain peak levels of 0.7-1.2Uml-1 after injection as per recommendations from the American College of Chest Physicians Consensus Conference on Antithrombotic Therapy for Prophylaxis in Patients with Mechanical Heart Valves [2,4,10]. This patient group requires diligent monitoring to ensure adequate therapeutic anticoagulation is achieved, with multidisciplinary input from obstetrics, haematology and cardiology teams at a tertiary centre.

Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO) is typically reserved for cases of severe refractory hypoxaemia, caused by respiratory or cardiac failure. VV ECMO is utilised to provide support in respiratory failure without circulatory compromise, whereas VA ECMO has a role in temporising haemodynamically unstable patients by also providing circulatory support, commonly through cannulation of aorta [11]. This allows time to stabilise the patient, treat the cause of circulatory collapse, or in the above case, and prepare for emergency surgery.

Although the majority of cases of ECMO have been described in non-pregnant patients, in the literature ECMO has been shown to have comparable outcomes in pregnant patients, with no significant maternal or fetal morbidity [6]. This is the first reported case with use of ECMO in the setting of treating valve thrombosis in a pregnant patient. We believe that it provided much needed haemodynamic stability and improved organ perfusion prior to surgery being undertaken.

The HACEK organisms ( Haemophilus aphrophilus, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella corrodens, and Kingella kingae ) were thought to be the most common agents involved in culture-negative endocarditis [15]. In a study from France more than 10% of all cases were found to be blood culture negative [16]. In our study 34 (68%) patients were blood culture negative. It is believed that these culture negative patients were possibly harboring HACEK organisms which were not identified. The most common reason for culture negative endocarditis might be due to frequent use of antibiotics by physicians to treat the condition empirically. Six patients were taking antibiotics among the culture positive endocarditis and 30 patients in culture negative endocarditis. Repeated blood culture before institution of antibiotics may increase the yield of culture positive results. For culture negative endocarditis serological and molecular methods can be used to find the possible HACEK like organisms.

References

- Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP 3rd, Guyton RA, O’Gara PT, Ruiz CE, Skubas NJ, Sorajja P, Sundt TM 3rd, Thomas JD; ACC/AHA Task Force Members. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients with Valvular Heart Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014; 129: e521-e643.

- Elkayam U, Bitar F. Valvular heart disease and pregnancy - Part II: Prosthetic valves. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2005; 46: 403-410.

- Basude S, Hein C, Curtis SL, Clark A, Trinder J. Low-molecularweight heparin or warfarin for anticoagulation in pregnant women with mechanical heart valves: what are the risks? A retrospective observational study. Bjog-an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2012; 119: 1008-1013.

- Schwartzenberg S, Perlman S, Levy R, Elkayam U, Goland S. Mechanical Heart Valve Thrombosis in Pregnancy. Journal of Heart Valve Disease. 2013; 22: 603-606.

- Nair P, Davies AR, Beca J, Bellomo R, Ellwood D, Forrest P, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe ARDS in pregnant and postpartum women during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Intensive Care Medicine. 2011; 37: 648-654.

- Sharma NS, Wille KM, Bellot SC, Diaz-Guzman E. Modern Use of Extracorporeal Life Support in Pregnancy and Postpartum. Asaio Journal. 2015; 61: 110-114.

- NICE. Anticoagulation-Oral National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). 2015.

- Iturbe-Alessio I, Fonseca MC, Mutchinik O, Santos MA, Zajarías A, Salazar E. Risks of anticoagulant therapy in pregnant women with artificial heart valves. N Engl J Med. 1986; 315: 1390-1393.

- Vahanian A, Alfieri O, Andreotti F, Antunes MJ, Baron-Esquivias G, Baumgartner H, et al. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012) The Joint Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for CardioThoracic Surgery (EACTS). European Heart Journal. 2012; 33: 2451-2496.

- Salem DN, Stein PD, Al-Ahmad A, Bussey HI, Horstkotte D, Miller N, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in valvular heart disease - Native and prosthetic. Chest. 2004; 126: 457S-482S.

- Ko CH, Forrest P, D’Souza R, Qasabian R. Case Report: Successful use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in a patient with combined pulmonary and systemic embolisation. Perfusion-Uk. 2013; 28: 138-140.

MedDocs Publishers

We always work towards offering the best to you. For any queries, please feel free to get in touch with us. Also you may post your valuable feedback after reading our journals, ebooks and after visiting our conferences.